Islamic shrines 🢔 Religious architecture 🢔 Architectural wonders 🢔 Categories of wonders

Wonder

Great Mosque of Djenne (Djenné)

In short

In short

Europeans may look in disbelief – is it for real? Does it exist? The Great Mosque of Djenne (correctly – Djenné) is as real as it can be – this magnificent structure is the center of the ancient Djenné city, it is physical and spiritual center of this amazing Sub-Saharan metropolis.

53.3%

53.3%

GPS coordinates

Architecture style

Age

Religion

UNESCO World Heritage status

Map of the site

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

In detail

In detail

Great Mosque of Djenne is one of the symbols of Mali and the whole of Africa – the largest adobe building in the world, the highest achievement of the Sudano-Sahelian architecture style.

History

Ancient West African city

Already some 2200 years ago (!) 2 km to the south of the present city developed Jenné-Jeno – one of the oldest urban centers in Sub-Saharan Africa.

This city was on the ancient trade route between the first West African empires and the Mediterranean – and thus it flourished. Back in those times, the floodplains of Beni were more fertile than now, the climate was milder. Caravans passed the city towards another legendary city – the 500 km distant Timbuktu (which in those times was much less significant) – and then headed into the giant Sahara desert, towards Morocco and Algiers.

Djenné developed in its present location sometime around 1000 AD and soon turned into a regional centre, a prosperous and impressive city. Some consider that it is even possible that the distorted name of Djenné – Guinauha – served as a root of a European term for Western Africa south of Senegal River – Guinea.

First mosque

According to stories, local king Koi Komboro (the 26th king of Djenné) was converted to Islam around 1280. He ordered to destroy his palace and build a great mosque in this place. The time of this construction is unclear – this could be as late as 1330.

In Medieval times this mosque and the madrassa next to it was an important center of learning – one of the most important ones in West Africa. Thousands of people came to this splendid city to gain knowledge.

Few Europeans visited this distant (for them) city until the 19th century. Some of the first descriptions of cities and mosques come from the early 19th century. Thus, French explorer René Caillié in 1828 saw an old, large building, which was rudely constructed, in a bad state, and abandoned. He wrote that thousands of swallows built their nests and the area was smelling bad. Locals were not happy to enter this crumbling structure and were praying in the outer court of the mosque.

It is well possible that this mosque was deliberately left to decay by the ruler, recent invader Seku Amadu. He considered this ornate building too pompous for Islamic values. Sometimes around 1834 – 1836, he ordered to build of a new, simple mosque next to the old one.

Shortly after 1893 the ruins of the old mosque were visited by French journalist Félix Dubois. In these times the interior of the mosque was used as a cemetery, there were just a few parts of the old building above the ground.

Return of the old mosque

In 1906 the rebuilding of the old mosque was started. It seems, this was an initiative of local people, but also the French administration helped in the organization of public works to build the mosque and madrassa next to it.

Works were directed by local mastermind Ismaila Traoré, head of the local guild of masons. The original fundament of the old mosque was used at least partly. Works were completed in 1907 or 1909.

Design of this structure surprised many Europeans. Some were amazed, some – very critical. Thus, Félix Dubois considered that this design has too much French influence. Later though it was recognized as the genuine design of local people – who, after all, have longer cultural traditions than most European nations.

Fashion incident

People in Djenné have used to multiculturality – here meet different nations and different ways of life. This is the border between the desert nomads and sedentary farmers of the Sahel. The city thrived on trade – and trade requires diplomacy and stability.

Thus – also the white infidels were welcome to visit the unusual Great Mosque of Djenne.

This lasted until an unlucky incident. Sometimes in the 1980s or in the 1990s a fashion photographer working for "Vogue" misused the hospitality of locals. He organized a photo session with scantily clad (how else!) women in this sacred building. Mullahs in horror watched all of this – and, alas, since then non-believers are asked to stay outside the mosque.

Conservation

Elsewhere the adobe mosques have been gradually modernized – with piping, electrical systems, and modern materials. The people of Djenné have been conservative (farsighted?) and have left the mosque in its original state. Thus today we see here the best, pure example of the specific local architecture – The Sudano-Sahelian style.

These efforts have been rewarded – the amazing architecture is admired by tourists and is creating new working places in this poor country. There would come more tourists if not for the political instability and warfare…

Architecture of the Great Mosque of Djenne

Unique city

Djenné today is a fast-growing city, with more than 30 thousand inhabitants. The city is poor – without proper sanitation, most people have not attended school.

This might be the poverty, but as well – memories about the great past, which have helped to preserve the architectural heritage. More than 2000 traditional adobe buildings have been preserved in Djenné – they are built and maintained by specialized masons – Bari. Sculptural forms of facades are not just for fun – they tell stories about the inhabitants of the house, although foreigners have no clue about this language of architecture.

Platform

Djenné is built on a floodplain island, which sometimes is inundated by the Beni River. This is dangerous for adobe buildings.

In order to save the mosque, there was build an enormous, 75 by 75 m large and 3 m high platform. This platform is accessed by 6 sets of stairs – each stair is adorned with pinnacles. The platform has never been flooded.

The open area in the front of the mosque earlier was a pond. It was filled with earth at the beginning of the French colonial period and now is used for the weekly market.

Adobe

Wast floodplains of Beni lack wood and stones – thus local people have no possibility to use these building materials. Due to the lack of wood, they cannot make baked bricks.

Thus just a mud can be used – but human genius finds a solution even in such a situation!

Local buildings are built from cylindrical mud bricks, which are held together with… mud. On top of this is laid a plaster made from… mud. All of this is dried in the hot sun of the Sahel.

This unusual material leads to rounded, soft forms. Adobe is not durable – it cracks from the temperature and moisture differences and is washed out by the rain. Thus regular (yearly) repairs are needed.

Sticks – scaffolding

Unique detail of large adobe buildings in the Sahel is the "sticks" protruding from the walls. These are bundles of rodier palm (Borassus aethiopum) which are intentionally cut off some 60 cm from the wall.

Bundles serve at least two purposes. First – they prevent cracks in the walls – they allow room for the wall to expand and contract in changing temperatures. Second – they serve as scaffolding for yearly repairs of the mosque.

Mosque

The Great Mosque of Djenne is not exact – in the plan, it forms a trapezoid. The main part is the 26 by 50 m large prayer hall, which takes up the eastern half of the building.

Eastern wall is directed towards Mecca and towards the main plaza. It is adorned with three massive towers – minarets, each topped with an ostrich egg. The tallest (20 m) is in the middle – the imam is conducting his prayers from this tower.

Wall is adorned with 18 pilasters – buttresses, each ending with a pinnacle.

Pyramidal elements in the design of Mali mosques are an interesting heritage from animist religions – these conical elements were the home of guardian spirits of ancestors.

The prayer hall is supported by nine interior walls with arches, thus creating 90 pillars inside this hall. Approximately 1000 people can fit inside.

Roof has removable ceramic bowls above vents – these are removed to let the hot air rise out from the premises.

Another half of the structure has no roof – this is an open court for prayer.

Yearly repairs

Great Mosque of Djenne is maintained in a unique yearly festival, where all people in Djenné take part.

Some days before the festivity the plastering is prepared in large pits. Boys are playing in this mud to stir it – this should be exactly the job each boy is dreaming about!

Adults also have their share of fun. On the day when repairs are done, much food is prepared. Masons take their positions on the scaffoldings and a race starts – who will be the first to bring the fresh plaster to the mosque?

Everyone is involved in this great and merry happening – and in no time the Great Mosque of Djenne looks freshly built.

Linked articles

Linked articles

Wonders of Mali

It is well possible that the most romantic African country is Mali. Like many countries in this beautiful continent, Mali nowadays has complex times, but in the past, it has seen prosperity, a flourishing of science, and political importance. Here developed several empires, were built enormous cities. Traces of those times have been preserved up to this day – in the highly unusual architecture, living traditions, ruins of once-prosperous cities, and art monuments.

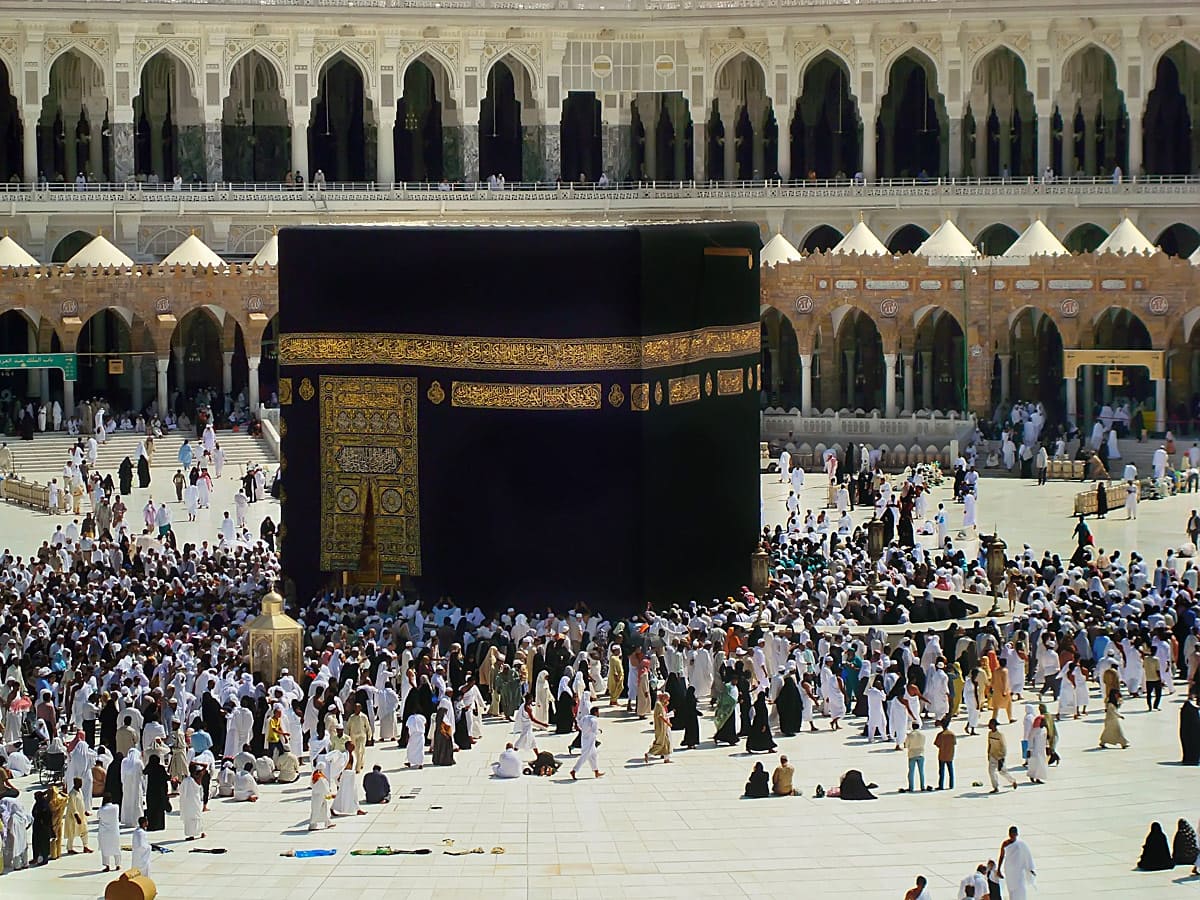

Islamic shrines

Place for worship in Islam is called a mosque. Mosques serve also for education, news exchange, and dispute settlement.

Initially, in the 7th century mosques were unpretentious, large halls for gatherings. Over time, as Islam was spreading, there developed diverse, locally adapted architectural forms of mosques.

Wonders of Africa

Africa has many outstanding wonders and some of the most surprising ones are the heritage of Egyptian civilization, the vernacular architecture of the Sahel region, tropical ecosystems, and others.

Recommended books

Recommended books

Butabu: Adobe Architecture of West Africa

Many think that sub-Saharan African architecture is little more than mud huts. Mud, yes–but certainly not huts. Instead, these adobe buildings, many of them enormous, show sublime sculptural beauty, variety, ingenuity, and originality. In the Sahal region of western Africa–Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Togo, Benin, Ghana, and Burkina Faso–people have been constructing earthen buildings for centuries.

Spectacular Vernacular: The Adobe Tradition

Spectacular Vernacular: The Adobe Tradition celebrates the beauty, variety, and efficiency of traditional adobe architecture in West Africa, Southwest Asia, and the American Southwest. In the severe desert climates of these areas, centuries of working with mud in the construction of homes, mosques, and whole villages have given rise to a remarkable range of styles and forms as visually stunning as any fabled city of myth and imagination – or any postmodern metropolis.