Caves 🢔 Geological wonders 🢔 Categories of wonders

Wonder

Krubera Cave

In short

In short

The world’s second deepest cave is Krubera Cave in Western Caucasus. This great monument of nature starts as a seemingly small hole high up in the mountains.

53.3%

53.3%

GPS coordinates

Location, address

Alternate names

Name in regional languages

Length

Depth

Map of the site

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

In detail

In detail

From 2001 to 2018 Krubera Cave was considered to be the deepest cave in the world. This small hole penetrates the mountains to a 2,197 m depth, just 15 m less than the world’s deepest cave – Veryovkina Cave some 5 km to the east.

Location and geology

Krubera-Voronya Cave is located in Arabika Massif, Western Caucasus. This is a very spectacular area, covered with dense forest (until the treeline at the height of some 1,800 – 1,900 m) and adorned with incredible mountain scenery.

Arabika Massif has been formed from an enormous shield of limestone that formed in the Upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous epochs. This limestone shield (which once was lying flat and smooth at the bottom of the sea) rises and folds over the last 5,6 – 5,33 million years and had been fractured with hundreds of larger and smaller fissures. The tallest summit here is the Peak of Speleologists, 2,705 m high.

Arabika Massif is part of a larger area of limestone mountains and is delimited by the deep canyons of Bzyb, Sandripsh, Kutushara, and Gega rivers as well as the Black Sea.

Krubera Cave is located in Ortobalagan valley – a comparatively shallow valley formed by glaciers.

Hundreds of caves

This mountain block contains several hundred caves and five of these caves are deeper than 1,000 m. Most likely these caves started to develop when mountains started to rise – more than 5 million years ago.

The formation of caves in Arabika Massif continues up to this day. The climate there is wet. A thick layer of snow forms in winter and the snow may close the narrow entrance to Krubera Cave. Each spring this mass of snow is thawing and causes flash floods. The water here is very cold (what slows down the karst processes) but abundant (what facilitates karst processes).

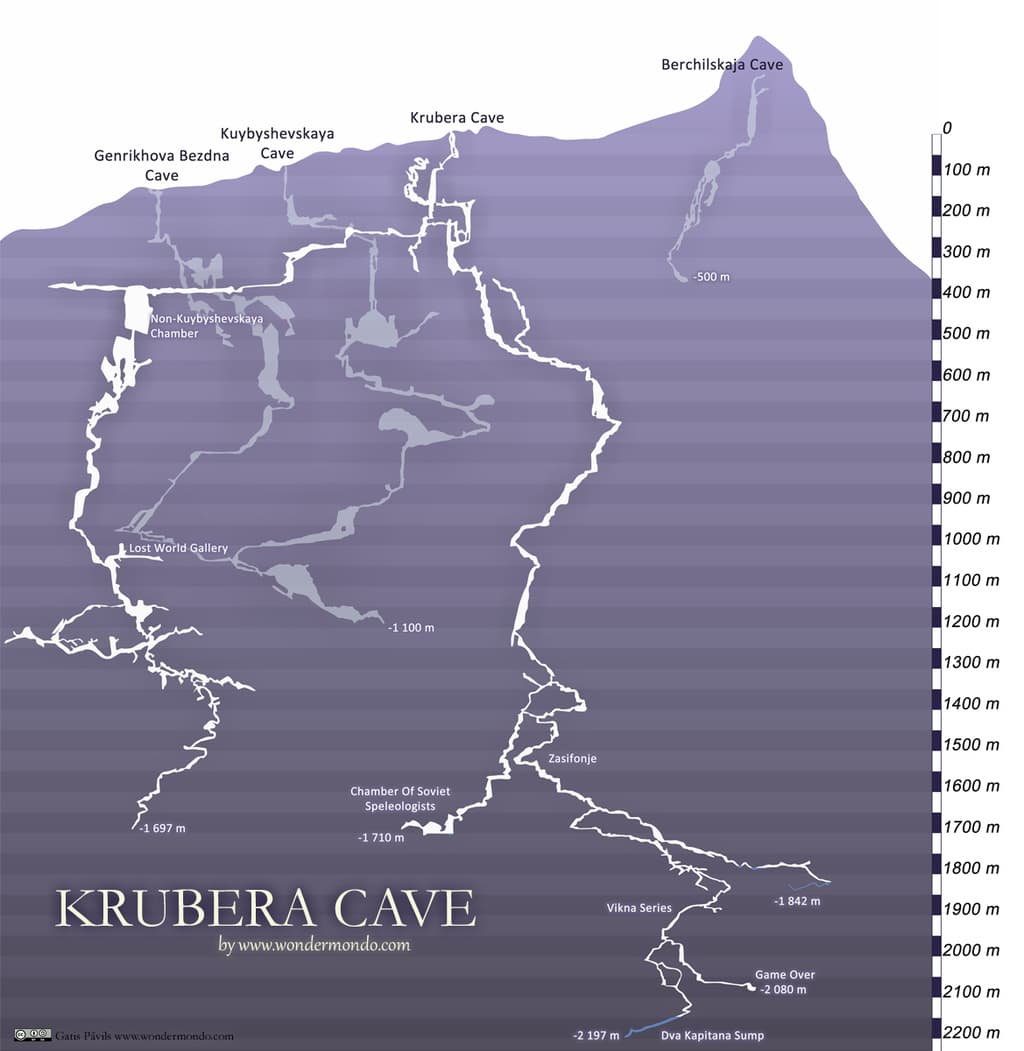

Deep caves of Arabika Massif are located closely together and their passages often meet, thus creating linked cave systems. Thus, another very deep cave in Ortobalagan Valley is the 1,110 m deep system of Arabikskaja Cave which includes Kuybyshevskaya Cave and Genrikhova Bezdna Cave (965 m) and it is possible that Krubera cave has a connection to it. Entrances of these caves are only 300 m apart from each other. Another very deep cave near Krubera Cave is Berchilskaja Cave which is explored to 500 m depth.

Description of Krubera Cave

Krubera Cave is a 16,058 m long cave system that for the most part consists of deep, vertical wells that are interconnected with passages. The deepest wells are 152, 115, and 110 m deep.

The cave starts high in the mountains, at a height of 2,256 m. The entrance is narrow and sometimes in winter, it may get covered with a deep layer of snow.

Krubera Cave often is very narrow – in fact, it can be penetrated thanks to the hard work of numerous expeditions that have carved many passages wider in order to pass through.

At the depth of 200 m cave divides into two main branches: Non-Kuybyshevskaya (explored to a depth of 1,293 m in 2008) and Main (2,197 m deep). At the depth of 1,300 m, the cave divides into numerous branches.

When speleologists descend to the depth of 1,400 m, there starts the next hardship – sumps (siphons). There are known 8 sumps up to the deepest part of the cave. Terminal (final, in the deepest part of the cave) lake – Dva Kapitana Sump – is the deepest one, it has been dived up to 52 m depth.

Water in the cave is very cold. At the 100 m depth, the temperature is just 1° C, and at 2,000 m depth it reaches 7.2° C. Air temperature in the cave is similar.

In winter the flow of water in the cave is very low, but in late May and June, it reaches the maximum, and the lowest parts of the cave are then inundated.

Where goes the water?

Speleologists most likely have reached the bottom of the cave lake – but the water goes further than this. It is not that easy to find where the water from Arabika Massif comes to the surface.

Cave researchers have added tracers to the water in the nearby Kuybyshevskaya cave. These tracers later were found in Reproa Spring and nearby Kholodnaja Rechka spring, as well as in a borehole that takes groundwater deeper than the sea level.

Reproa Spring (located approximately at 43.331534 N 40.204696 E) is a very interesting natural monument – it is a powerful spring with an average discharge of 2,500 l per second and it forms one of the world’s shortest surface rivers which after 18 m falls into the Black Sea. The distance between Reproa Spring and the entrance to Krubera Cave is 12.75 km.

The deepest point in Krubera Cave, at a depth of 2,197 m, is located only 59 m above sea level. Thus one could assume that this cave cannot go much deeper than this.

Research shows that caves here could continue well under the sea level. This is testified by amazing undersea springs deep in the Black Sea. Thus, a group of springs can be seen near Tsandripsh at the depth of 5 – 7 m, there are known other submarine springs but one spring has been marked during hydrological research at the depth of almost 400 m!

This might seem like a mystery – how could freshwater go that deep under the sea level? But we need to take into account the geological history of this amazing part of the world. More than 5 million years ago the Black Sea almost dried up – and most likely caves formed already in these times and these ancient cave systems have “survived” up to this day when the sea level is much higher.

Thus, analysis of stalagmites from Krubera cave (230Th dating), taken in the depth of 1,640 and 1,820 m testifies, that these cave formations are more than 200 thousand years old – this is a significant age.

Cave biology

This unique cave has some biological peculiarities too. Here live more than 12 species of arthropods including some endemic species: springtails Anurida stereoodorata, Deuteraphorura kruberaensis, Schaefferia profundissima, and Plutomurus ortobalaganensis. Here lives also near-endemic beetle Catops cavicis, which has been found also in some nearby caves.

Plutomurus ortobalaganensis is the deepest living terrestrial animal on Earth, found up to 1,980 m deep. This collembola is 3 mm long, without eyes and most likely feeds on fungi and organic matter coming from above.

History of exploration

Krubera Cave was discovered by Georgian speleologists (led by L.I.Maruashvili) in 1960. It was named by them after A.A. Kruber (1871 – 1941) – an outstanding Russian geologist and researcher of karst processes. Georgians back then explored it to the depth of 95 m – further advance was hindered by impassable squeezes.

In 1968 it was further explored (to the depth of 210 m) by an expedition from Krasnoyarsk and named – Sibirskaya Cave.

Further advances in exploring this cave (and other caves in Arabika Massif) were made mainly by Ukrainian speleologists. There was a period in the early 1980s when many speleologists believed that caves in Arabika Massif are not too deep and not too interesting. The persistence and good organization of works by Ukrainian speleologists proved the opposite. From 1982 to 1987 Krubera Cave was further explored by Kyiv speleologists (they reached a depth of 340 m) and then it got the name Voronya Cave (after a number of crows nesting near it). Speleologists were hard working to widen the narrow passages in order to squeeze through them – and some report that it was even a kind of mysterious feeling fuelling their efforts.

Only in 1999, when the political situation calmed down, exploration continued and since then have been achieved surprising results – Krubera Cave turned out to be the deepest known cave in the world! Ukrainian expedition in January 2001 reached world record depth (exceeding 1,710 m), and a few years later, in 2004 for the first time in the history of speleology, the explored depth of cave exceeded 2 km.

In 2012 Gennadiy Samokhin (Ukraine) reached the current depth of 2,197 by diving 52 m deep in the terminal lake.

Cave now is a very popular destination for expeditions coming from many countries, as it is a kind of “Everest” in speleology.

Currently, speleologists focus on the exploration of other passages in the hope to connect Krubera Cave to other nearby caves and reach a more significant length of the cave.

References

- Alexander Klimchouk, Krubera (Voronja) Cave. Encyclopedia of Caves, edited by William B. White and David C. Culver, 2012.

- Alexander Klimchouk, Yury Kasjan. In a search for the route to 2000 meters depth: The Deepest Cave in the World in the Arabika Massif, Western Caucasus. Accessible on CaveDiggers.com, 30 March 2014

Linked articles

Linked articles

Wonders of Georgia

There are few small countries in the world with such a distinct culture and richness of natural and man-made landmarks as Georgia. Here evolved several distinct writing systems, own architectural styles, and art styles.

Caves

Every year there are reported exciting discoveries of new caves and discoveries of new qualities such as cave paintings in the ones known before. But there still is a feeling that our knowledge covers just a small part of all these monuments of nature.

Though, those which are known to us, offer a surprising diversity of unusual features and impressive sights.

Ecosystems

Biotope is a rather small area with uniform environmental conditions and a specific community of life. Wondermondo describes biotopes and ecosystems which have striking looks, look very beautiful, or have other unusual characteristics.

Recommended books

Recommended books

100 of the Deepest Caves In the World

Are you looking for a journey that will take you through 100 of the Deepest Caves In the World, along with funny comments and a word puzzle? Then this book is for you. Whether you are looking at this book for curiosity, choices, options, or just for fun; this book fits any criteria. Creating 100 of the Deepest Caves In the World did not happen quickly.

Geomorphology of Georgia

This book is based on the results of several years of geomorphological studies and research in Georgia, published for the first time in English, and covers a gap in research in the field of world regional geomorphology.

[…] Fonte: 1 2 […]